In July 2016. The Pennsylvania General Assembly passed a 40 percent wholesale cost tax on vapor products. This tax, which was highly controversial and drew a strong response from free market advocates, the media, and hundreds of small vapor business owners, went into effect October 1, 2016. Since the passage of the tax, at least 130 small vape shops, retail operations dedicated to getting cigarette-addicted adults off of deadly combustible cigarettes, have closed their doors permanently or moved operations out of state. For the sake of disclosure, I owned a business such a business that was closed as a direct result of this tax.

This tax contained an onerous “floor tax” provision that required small mom and pop shops to take an inventory on or about the day the tax went into effect, and assume a tax liability equal to 40 percent of the wholesale value of their entire existing inventory on that day. Payment of this tax bill was due in full by December 29, 2016 – just under three months after the tax took effect. If a small mom and pop vape shop had $50,000 in inventory on the day the tax went into effect, they would have been directed to pay the Pennsylvania Department of Revenue $20,000. Floor taxes have been the status quo in cigarette taxes for years, but the entity primarily responsible for paying cigarette floor taxes has traditionally been heavily capitalized, bonded warehouses that wholesale cigarettes to retailers.

The Department of Revenue estimated that the 40 percent tax would bring in $13.3 million dollars in the first year (a small fraction of the $100 million-plus they get from cigarette taxes). It looks like they exceeded their projection, but at what cost? This tax was partially or completely responsible for the closure of over 130 small businesses in the state. Each of these businesses had, on average, three or four employees and likely did an average of $250,000 in business per year. The regulatory state rarely if ever gives serious consideration to negative impacts. They certainly don’t factor them into their revenue reports.

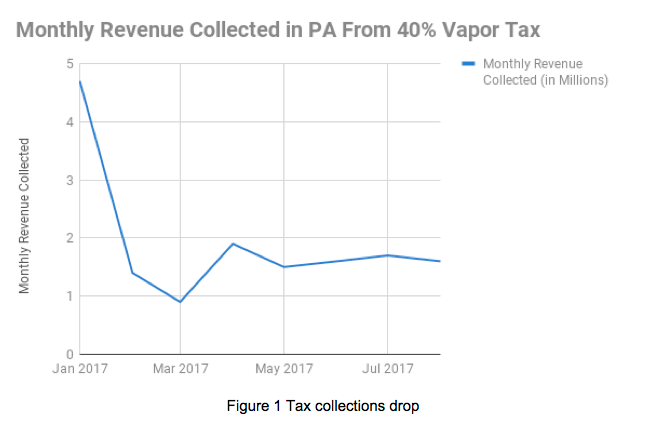

Numbers provided by the Pennsylvania Department of Revenue paint a grim picture of the effect the tax had on economic activity (see chart below). Monthly tax collections (excluding floor tax payments) have dropped by almost two-thirds from January to August. It’s fair to assume that this is indicative of a devastating drop in sales at businesses in the category. It’s probably also fair to assume that most of this drop results from both border bleed and online bleed. Consumers in PA are free to buy the products they used to get from their local vape shop from any of the thousands of online retailers that ship products to PA daily, without having to pay the tax up front (federal law prevents a state from forcing an out-of-state business to collect and remit a state tax from another state). The tax stipulates that consumers are required to “self-report” and file a special tax return with the PA Department of Revenue monthly, but it is unlikely that even 1 percent of consumers do this, or even know they are required to. It’s also highly unlikely that PA has the resources to enforce such a requirement. Certainly also many PA residents that had made the switch have now, unfortunately, returned to smoking.

Data provided by PA Department of Revenue

How have the remaining vape shops survived the tax? The answer is complex and varied. Certainly a contraction in the number of shops has meant that remaining shops can pick up some customers from closed shops. Also, many distributors selling into the state have offered reduced rates on e-liquid to PA wholesale clients to help absorb the impact of the tax. Virtually no such deals for shops exist on hardware (batteries, mods, tanks, coils, etc.) that are sold at much tighter profit margins. The net effect of this is the conversion of vape shops from full service retailers that can affordably offer adult smokers everything they need to switch (including training), to essentially e-liquid shops. Presenting obstacles to adult smokers who want to switch can be expected to get smoking rates in PA gradually tracking back upward.

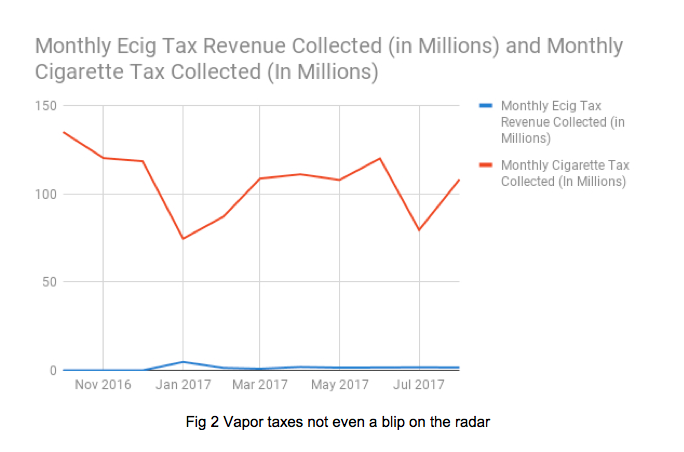

One might wonder how a policy that has such predictably negative economic and health consequences for both PA consumers and small businesses could come to pass. The biggest answer is money. PA collects over $100 million a month on cigarette taxes, an amount that dwarfs vapor tax collections (see chart). Elected officials in PA have demonstrated time and again that they know almost nothing about e-cigarettes and vaping. But one thing they do know is that almost every one of the 400,000 adult vapers in PA was a smoker first. When tobacco taxes first began to be proposed in the US, they were sold as a way to discourage the use of cigarettes. Today in a time of tight budgets and seemingly insurmountable deficits, legislators view smokers as a source of revenue. They have, in effect, become addicted to cigarette taxes in the same way smokers are hooked on cigarettes. It’s not hard to see that as vaping came along they would view it more as “a new type of smoking” to tax, than a low harm solution to the smoking crisis in America. They need to find a way to replace cigarette tax revenues lost by people switching to a product that was often recommended by their family doctor. People switching back, or not switching in the first place, protects typically dwindling cigarette tax revenues.

Data provided by PA Dept of Revenue

Another supporter of vapor taxes are “public health” groups. These groups typically (and coincidentally) have very close relationships (financial and personal) with the same pharmaceutical companies that make nicotine patches, lozenges, and gums, as well as cessation drugs like Chantix. These groups spend tremendous amounts of time and money lobbying legislators in support of such policies. Most of the people and lobbyists from these groups that meet with legislators likely know nothing about their organization’s ties to drug makers, so it’s very unlikely such a conflict would be revealed.

Screenshots via NY Daily News/Drugfree.org

Now that over 130 small businesses have closed since this tax has passed, what can and should be done? It’s clear that the tax should either be amended or repealed. Last year, State Rep. Jeff Wheeland proposed amending the tax to 5 cents per milliliter on e-liquid at the point of sale. His proposal had incredibly strong bipartisan support but was bogged down by procedural moves in the House, and was never allowed to come to a vote at the end of the last session. Had it passed it would have allowed dozens of small vape shops to reopen. It likely also would have generated only slightly less revenue than the 40 percent tax.

Perhaps the best way forward would be for the state or a private entity to do a thorough economic impact assessment on the tax. PA taxpayers deserve nothing less than a full picture of the effects of taxes like this that result in widespread business closures.

Chris Hughes is a former vape shop owner in PA, and former President of the PA Smoke Free Alternatives Trade Association.